Discovering Alzheimer's Disease

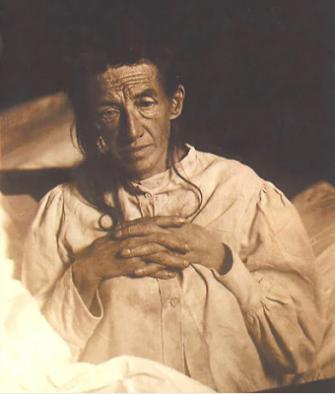

Auguste Deter, better known as Auguste D., is credited as the first individual to have been diagnosed with Alzheimer's Disease. Mrs. Deter was born in Germany during 1850, residing in her home country her entire life, until her passing in 1906. Before her hospitalization at fifty years old, Mrs. Deter was known to live a very quiet life; she seemed to greatly enjoy her responsibilities as a homemaker to her husband and children. However, before her fiftieth birthday, the Deter family and their neighbors noticed changes in Auguste's behavior. Mrs. Deter was described as experiencing progressively severe cognitive, emotional, and motor-skill changes. At first, Mrs. Deter began to struggle with her short-term memory, which was quickly followed by abnormally angry and/or jealous outbursts. Soon after, these symptoms began to worsen, and she also began experiencing extreme paranoia and was unable to maintain a normal sleep-waking cycle. Unfortunately, Mrs. Deter's symptoms only continued to progress, and her husband had to make the difficult choice of hospitalizing her. The Community Psychiatric Hospital in Frankfurt was the epicenter of discovering Alzheimer's Disease.

(Hippius, The Discovery of Alzheimer's Disease.)

Interestingly, Auguste Deter's diagnosis of Alzheimer's did not come until years after her death. Even though multiple doctors and institutions had looked over Mrs. Deter's symptoms, tissue samples, and cause(s) of death, it was not until similar cases were examined that the disease and pathology were named. While Auguste was under the care of doctors at the Community Psychiatric Hospital, every interview and progressing symptom was carefully recorded and analyzed. Mrs. Deter was also personally aware that her memory and abilities had begun failing her. When she was aware that a particular skill or memory was now out of her capability, she would note it herself to staff. For example, upon not being able to recall her name or marriage properly, Auguste flatly said, "I have lost myself." Even though "senile" conditions had been recorded throughout history, Auguste's condition was viewed as abnormal; based on the current beliefs, "senile" cognitive afflictions only occurred in the elderly, yet Auguste was only fifty, didn't have "previous instability," and her symptoms were just as progressive and severe. Therefore, doctors were perplexed at what could be causing her symptoms. This led to a general questioning of why "becoming senile" had not been further examined, and if these symptoms instead were the sign of a cognitively degenerative disease.

(Braak, et al., Staging of Alzheimer Disease-Associated Neurofibrillary Pathology Using Paraffin Sections and Immunocytochemistry; Hippius, The Discovery of Alzheimer's Disease.)

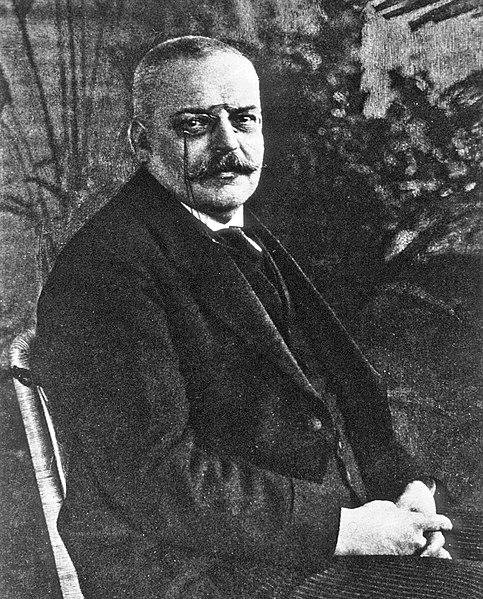

Dr. Alois Alzheimer was born and lived within multiple areas of Germany throughout his lifetime. Soon after finishing higher education, Dr. Alzheimer decided to work at the Community Psychiatric Hospital for Mental and Epileptic Patients in Frankfurt. Throughout his career, Dr. Alzheimer worked with such a diverse caseload that his title would be considered as a Clinical Psychiatrist, instead of a general neurologist or psychiatrist like he imagined. While working at the Frankfurt hospital, Dr. Alzheimer began working closely with Dr. Nissl; this pairing is attributed to being a vital aspect of discovering Alzheimer's Disease, as Dr. Nissl had just discovered a tissue-staining technique. The Nissl stain is currently still used throughout medical research and was the major staining technique Dr. Alzheimer used in order to view amyloid plaques. This same Frankfurt hospital is where Auguste Deter was admitted, and Dr. Alzheimer led her full intake appointment. Almost immediately, he realized that Mrs. Deter's symptoms seemed significantly abnormal, and so he and his team took rigorous notes on her condition and its developments.

(Birchtold, Evolution in the Conceptualization of Dementia and Alzheimer's Disease: Greco-Roman period to the 1960's; Hippius, The Discovery of Alzheimer's Disease.)

*Warning: human tissue samples will be discussed, viewer discretion is advised.*

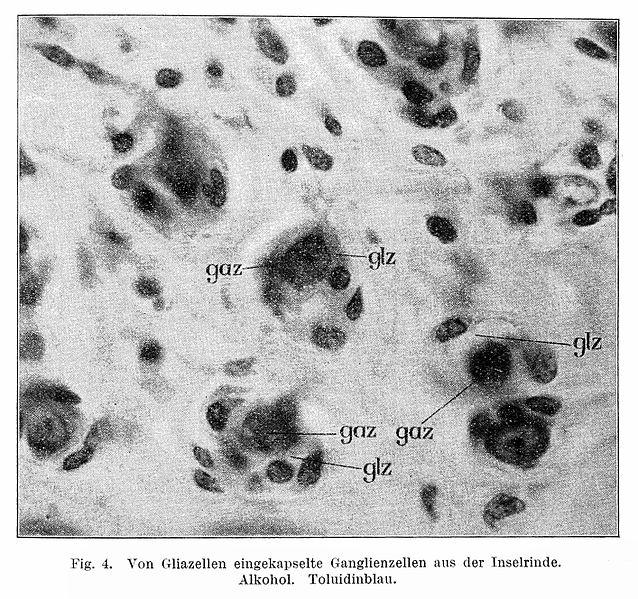

Within modern day research and clinical settings, Alzheimer's Disease can be visualized in numerous ways, including noninvasive techniques. Diagnosis is typically done via cognitive and movement testing in a generalized clinical setting, with follow-up blood work and/or brain imaging. However, when Dr. Alzheimer and colleagues were first discovering the disease, Alzheimer's pathology and effects could only be visualized with post-mortem tissue samples. Though this vastly improved how Alzheimer's Disease was understood, it didn't help the patients currently experiencing cognitive decline in any way. This is the main reason researchers are moving towards noninvasive imaging techniques; the goal is for individuals to be able to be successfully treated without discomfort while origins of the disease are being studied.

Though imaging and experimental techniques have advanced and vastly changed throughout the years, the hallmark pathology markers of Alzheimer's Disease have stayed consistent. Within both tissue samples and high-powered, noninvasive imaging techniques, clinicians find distinct aggregates of abnormal proteins within specific brain regions. These aggregates of beta-amyloid plaques and tau tangles deposit themselves within specific brain regions over the course of the disease, and as their progression spreads, symptoms typically progress. The presence of these protein aggregates is such a hallmark of the disease, that they are the major defining difference between Alzheimer's Disease and other dementia types (this defining nature has been upheld throughout the course of the disease's discovery).

(Braak, et al., Staging of Alzheimer Disease-Associated Neurofibrillary Pathology Using Paraffin Sections and Immunocytochemistry; Hippius, The Discovery of Alzheimer's Disease.)